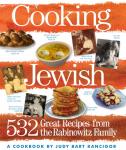

BUY COOKING JEWISH by clicking here now.

Nature's cues signal Rosh Hashanah

The Orange County Register

September 9, 2004

by Judy Bart Kancigor

When the exotic yellow Barhi date first appears in the open-air markets of Israel, no one needs a calendar to sense that Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, is approaching. So, too, did the ancient Hebrews mark the seasons with cues from nature - the ripening of wheat in spring, the profusion of figs in summer, pomegranate harvest in fall, the pressing of olives in winter.

Rosh Hashanah, which starts at sundown Sept. 15, began as an agricultural festival and might have remained so if not for the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans, which forced the Jewish people into exile. "The Essential Book of Jewish Festival Cooking" by Phyllis Glazer with her sister, Miriyam Glazer, (HarperCollins, $29.95), explores, through mouthwatering recipes and their fascinating origins, how the holidays were remolded by the rabbis and sages in the Diaspora.

"There were no familiar signs of nature for the people to follow in their new land," Phyllis Glazer explained, visiting from her home in Israel, where she is a cookbook author and well-known food journalist. "The rabbis sought to save the holidays and give them other meanings.''

"There's a beautiful line in one of the Psalms: 'How can we sing the Lord's song in a strange land?' " added Miriyam, a professor of literature and a rabbinical student at the University of Judaism in Los Angeles. "And so the rabbis looked for scriptural evidence in the Bible itself in order to preserve the festivals."

While the Bible mentions a day for blowing of the shofar (ram's horn), there is no evidence of a holiday called Rosh Hashanah. "Centuries later Rosh Hashanah evolved," noted Miriyam, "because, although our new year had been in the spring, the culture our ancestors were living in had a new year celebration in the fall. All the holidays as we know them today are products of hundreds of years of discussion that are captured in the Talmud."

Over the centuries, as the Jewish people found themselves dispersed across the globe, traditions were added to the observance of the festivals. For Rosh Hashanah, we dip apples in honey to wish each other a sweet year. We eat carrots, because the Yiddish word for carrots, merren, also means "increased," so we wish for "increased" health and prosperity at this time.

Challah, the egg bread so inextricably linked with every celebration, takes various shapes for each holiday."I learned to braid my hair by learning to braid challah," Phyllis recalled of her mother's Sabbath loaf.

On Rosh Hashanah, we create grand spirals to dip in honey. "Since Rosh Hashanah also celebrates the creation of the world, the round challah is a symbol of the holiness of life and the life cycle, the endlessness of life," said Miriyam. "We add raisins for the same reason that we dip apples in honey, to enjoy a sweet new year."

Because Rosh Hashanah comes at the beginning of the lunar month when the moon is hidden, we eat "hidden" foods. "That's echoed in food like kreplach (meat-filled dumplings), in which you can't see what's inside," noted Miriyam, "just as the moon is hidden at the holiday."

Pomegranates, too, assume a special place on the Rosh Hashanah table. "It's a blessing to eat a food at Rosh Hashanah that you haven't eaten in that season yet," said Miriyam. "That's why we eat pomegranates at Rosh Hashanah when they have just come into season." This ancient fertility symbol was even used to make wine, the Glazers point out, as we see in the Song of Songs.

Wine is so central to Jewish festivals that the grape is the only fruit that has its own special blessing. "Every sacred meal begins with a glass of wine," said Miriyam, "but the wine of our ancestors was very different from ours. They had to dilute it, because it was like a thick syrup. Today Israel has really reclaimed and developed beautifully the wine industry, so all these new and really fine wines are coming out of there. Many people associate kosher wine only with the thick, sweet wine that used to exist 50 years ago, but today they have the finest and a wide variety."

Grapes are one of the Seven Species of the Bible, the special foods that best portray the land and its traditions, a list that also includes wheat, barley, figs, pomegranates, olive oil and honey.

"Seven is a magical number, mystical number in the Jewish tradition," observed Miriyam. "The world was created in six days, and on the seventh day, God rested. The Seven Species are all over the tradition. We see them as evoking the whole spiritual path from the fulfilling of the basic needs of a human being, wheat and barley, to the sweetness of honey. We believe that they map a whole spiritual process."

RECIPES

Roasted Eggplant And Pomegranate Seed Salad